David Byrne and Nick Hornby turned me onto John Carey’s What Good Are the Arts, a manifesto against objective aesthetics. I’ve never met David Byrne or Nick Hornby, but they’ve both written so reverently about that book in a way that resonated with my existing thoughts about art that I knew I’d be into it. Carey picks apart the themes of “good” and “bad” art or “high” and “low” art in such a way that clearly shows the absurdity of the idea that our tastes adhere to any sort of intrinsic objectivity.

Popularity plays a role in how things are passed down through time, and oftentimes the way things are rediscovered relies mostly on pure chance. Two examples that come to mind are Moby-Dick and Stoner, both of which relied on posthumous reprints that spurred other writers to proselytize the merits of those works. Or the outsider art of Henry Darger being discovered by his landlords. Even the term “outsider art” seems to imply a sense of interest in art made by people who are “not us”. “Us” in this case being the established art world.

I firmly believe that everyone has the ability to create art, and although their might be biological underpinnings that make certain people more adept at certain mediums or more driven to pursue it, I think that the main determinant is encouragement received and resources available. Success in the art world depends on the subjective tastes of the members and whether you can appeal to their sensibilities.

We live in an age now where gatekeeping is still very much in place but also easier to get past. There’s no way to stop the inevitable extinction that’s always happening, but it is easier to dig for the obscure and try to give it some light.

Rather than listening to established voices in art and criticism, I’ve always pushed the idea that you can also find art through the art that you like. I wouldn’t know about John Carey if I didn’t follow up after reading Byrne and Hornby. I wouldn’t know about KRS-One if I didn’t look for him after hearing Sublime’s song (and I know because of KRS-One). I wouldn’t know about John Sloboda if I didn’t hunt down Ani Patel’s sources. Follow the footnotes.

Check out the Weird Music album on Bandcamp, iTunes, Apple Music, Spotify, and all other places where you can find music. Some of this material can also be found in the post “My Weird Music” on the Talking Writing website.

One thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is how much great art is constantly being made that will never get heard or seen by anyone, let alone make its way into the future. There are many pieces and artists that we know about that weren’t appreciated until years after their releases or deaths. Moby Dick, Stoner, Emily Dickenson, Van Gogh, Otis Redding, Bach. And even some artists get the recognition within their lifetimes, but it doesn’t come until years or decades after the work was created.

But what about all the art that just gets dropped into the oversaturated ocean of the digital landscape and will never see the light of day because no one pays attention? What about all the art that gets made but the artist doesn’t feel comfortable showing it to anyone for fear of criticism? What about all the art that never gets finished because the artist couldn’t stop tweaking it? Weird Music could easily be or have been in any of these categories.

And even though I keep my eyes and ears as open as I can, I’m fully aware that my musical taste and awareness is only a tiny fraction of all the art that I would like. There’s never been any way to find all the music that would appeal to you, and even though discovery is easier than ever now, the depths of the ocean are even deeper. And the deeper the water, the less light there is.

Drew Daniel: I never would’ve thought that kids would be making weird cassettes in 2009. The cassette seemed completely dead, but now it’s exotic and kitsch and funny to people that were born in 1990. To them it’s hilarious.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, the massive overreaction, the way people despise compact discs is quite surprising to me. It’s too bad because I think it’s a good format. The art is horrible, visually they're horrible.

Drew Daniel: But I like seventy minutes more than forty minutes with some artists. With others it’s a disaster.

Martin Schmidt: The sound quality is great. I think it’s too bad that people hate CDs.

It kind of doesn’t matter to me what the object is. I wish they had made CDs this big [forms hands in shape about the size of a record]. Ecologically speaking, that’s bad. Making bigger plastic discs in larger paper sleeves is bad, but we’re making art here, people. It’s art, it’s not prudent.

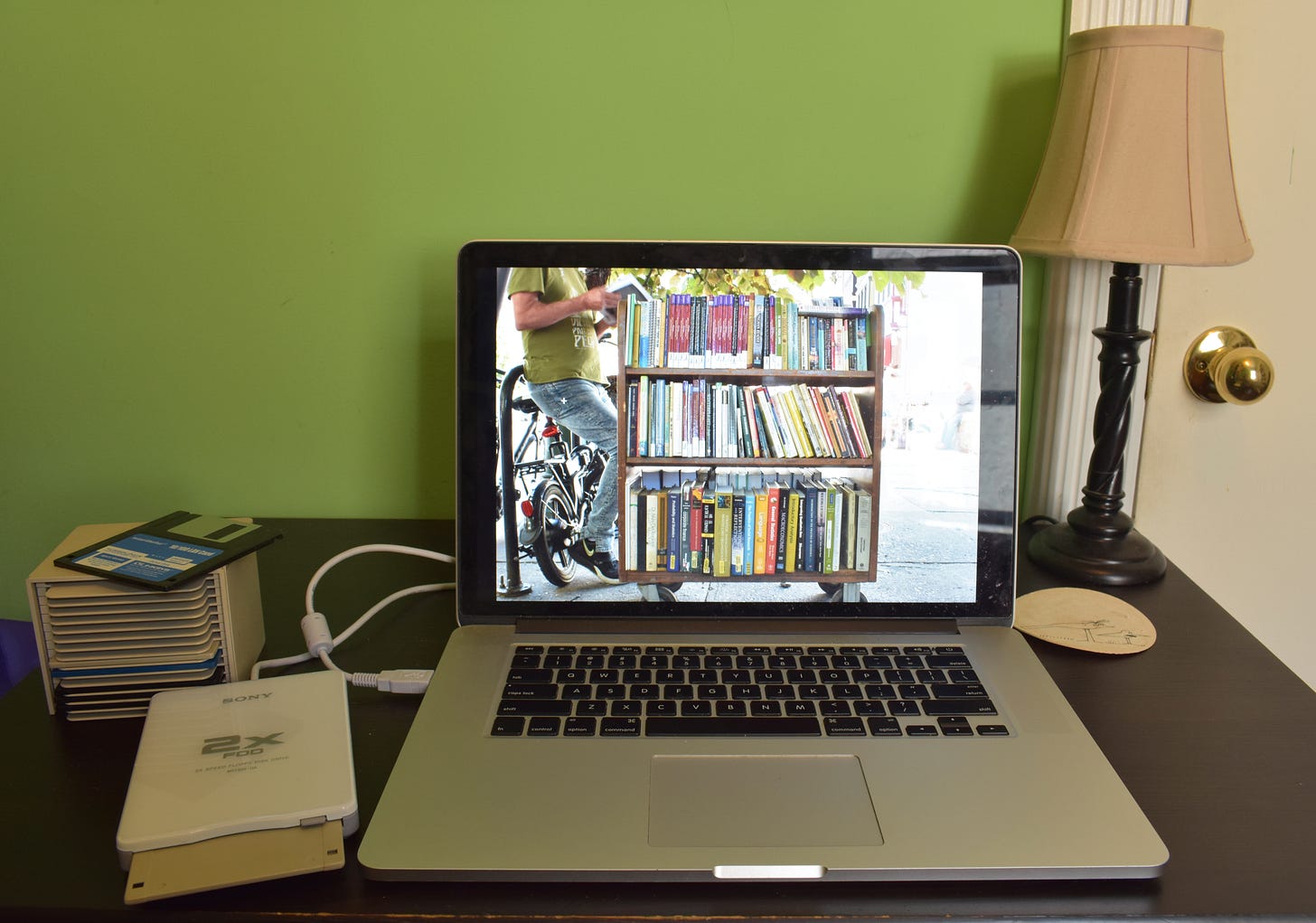

So, obviously ecologically, digital distribution, great. I sincerely doubt that the kids that I met eight years ago, ten years ago, still have those songs. I have a fucking record that I bought in 1981 and I love it. And I still love it, and it still plays, not quite as well as it did in 1981, but almost. I have this revered object that’s historical and I have it thirty years later or however long ago that is. I don’t think they’re going to have that file on their computer thirty years from now, and that breaks my heart because I treasure that shit.

I have this record New Music for Recorded and Electronic Media that has Pauline Oliveros and Laurie Anderson and Laurie Spiegel all together. People who continued to make {laugh}—in most cases—great work. How many people I’ve played that record to. And when you play a record, here’s this record that you’re listening to and you hold it in your hands and you listen to it and you can read a little bit about it. All that, gone with files, besides the fact that twenty years from now you aren’t playing that anyway because you didn’t even have it.

Drew Daniel: The dematerialization of the object can seem very revolutionary and subversive, like, “Why do you need all these possessions, man?” There’s this economic appeal of the unleashed anarchy of everyone can own everything and no one owns anything because there’s no thing there anymore, and that’s great.

But from the point of view of history and survival, it’s scary to think about how slender these connections are. You can open it because your software understands the file architecture of this file and the header on this file and thus it can be opened. But I wrote all kinds of things that meant a lot to me that I stored on 3.5 inch diskettes that computers used to be able to read in 1994. And I can’t read my diaries from college anymore. Or maybe I could find someone who’s an archivist who has the converter. People don’t really see that they’re giving away a lot when they’re abandoning the material culture for an entirely digital culture.

And the sad fact is that digital doesn’t mean dematerialized. There are servers that exist somewhere that have to get powered, that are owned by somebody, and when you are uploading and storing, there’s a set of financial transactions and a set of government bureaucracies that are regulating and making that access possible.

Martin Schmidt: That fucking nightmare, the thing I read recently about the Kindle, the Amazon e-book thing. Which, I’m a techno dude, I think it’s a fucking rad idea that the New York Times is delivered to my thing, and I have it for today and then I can delete it. It holds 1000 books on it, and it’s this thick and I can carry it around and it practically takes no power. Awesome.

But this is just an example a couple weeks ago. Apparently Amazon had been selling an unlicensed version of 1984 by George Orwell, hilariously fucking enough. So they reached out and deleted it off of everyone who had bought its Kindle. In the world. Without asking them.

Drew Daniel: So everyone had bought this book, thought that they owned this digital book, and that their e-book was just as good as a material book, except they didn’t realize that the corporation that had sold it to them could just take it back whenever they wanted.

Martin Schmidt: And they refunded them their $6.95. So there’s no harm done, right? That we reached into your library, removed a book and burned it and here’s your seven dollars back.

Drew Daniel: And the New York Times article didn’t even note the crushing irony of this idea, “What do you know, a book about a totalitarian civilization is exactly the one that now this digital, corporate friend of yours that guesses what you want to read and proposes that, ‘You like this, you might like this, too,’ and ‘I know that you have this book, this book, and this book. Oh, and actually I need this back. And I’m just going to take it from you.’”

Martin Schmidt: I’m not even going to tell you! When you look for it it’s just not going to be there.

Drew Daniel: If some crusty punk band described a scenario like this in their lyrics, you’d be like, “Yeah, yeah. Give me a break.” And then it actually happens and you realize, “Well, I’m glad no one can delete the Crass record that I have over there.” I actually have it, it’s too late. So long, suckers, it’s in my house.

There’s a creepy Gollum-like side to record collecting, the “my precious” of this rare punk record that I have and you don’t. And that’s lame. I like that digitally I can now hear incredibly rare noise cassettes by Étants Donnés that I’ll never find because there were fifty of them that were sold in France in 1980. I love the Internet for that reason.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, that part is fucking rad.

Drew Daniel: It is an archive and it is a way of preserving and connecting that’s really magical in certain ways. But I think it should be a material culture plus the Internet, not Internet instead of a material culture. And economically, it’s sad to say, but there is a shrivel that’s happening as a result of the fact that now everything is free.

If you’re fundamentally a consumer then you win and that’s great for you. But if you’re fundamentally a creator, and it costs you a few thousand dollars to press up your CD, it costs a couple thousand dollars to get a new computer when your computer dies, and when the neck of your bass cracks and you gotta replace your bass guitar, that money has to come from somewhere.

Martin Schmidt: And now it can’t come from music. It has to come from your regular job.

Drew Daniel: So we slide back a few steps with that model.

And here’s where everyone jumps up and down and goes, “Springsteen did Nebraska with a four-track!” and “A lot of those Misfits records were recorded with one mic!” and “You don’t need a fancy studio to make great art, man!” No shit, I know that. But you can’t make Billie Holiday Lady in Satin with a full orchestra with just a TEAC digital recorder. You need a full orchestra and the mics and the engineers and the real studio.

There are certain kinds of art that can only be made on a grandiose, lavish scale in that it can only be maintained by a real studio system. So we’re losing something.

Martin Schmidt: People like Steely Dan, not a band that I particularly love—okay, I kind of love them, whatever—but they are an absolutely unique expression of an insane amount of recording technology.

Drew Daniel: And money.

Martin Schmidt: Years of expertise by a bunch of people who did nothing but freak out about recording technology and techniques all the time. Their shit is the ne plus ultra of late 70’s recording technique, which, in the model today, and especially where the model is going, nothing like that will ever be possible. And that was a beautiful, unique thing. I suppose there will be more beautiful, unique things and all is all and everything will be fine because that’s the way it is, but.

Drew Daniel: It’s weird when you hear now, “You know what? They don’t make new studio recordings of opera.” They can’t afford it. To record an orchestra is about forty to sixty thousand dollars a day. The audience for who wants to buy new recordings of opera is not large enough to support the studio expense of that. So what you have instead is a video recording of a live performance, but there aren’t studio recordings of opera because the iceberg melted.

We have this idea of ceaselessly adding, that we do nothing but progress and it keeps getting better. We keep having more options and more things to buy, of course. That’s the American model, your freedom is your freedom to shop and consume. But there isn’t so much of an awareness of, “Well, what do we lose? What forms of extinction are happening?”

Chris Powell: One thing that I actually did want to mention that I feel very strongly about is, regardless of the artists losing money and all the negative things about it—there’s the negative, there’s the positive—one thing that I think is a really negative effect of all this is studios closing, records overall sounding not as good. People are getting better at making recordings at home, but now because of the whole game changing, everyone has to find new ways to make a record. Recording budgets are gone now, so everybody has to fend for themselves and figure out a way to do it. I think it’s good for people to learn how to do those things, but overall records are not sounding as great and a lot of people listen to it on little computer speakers, which is just awful {laugh}. At least get a good pair of headphones, for our sake {laugh}.

People listen to it on tiny speakers or just really lousy headphones, so you’re not necessarily hearing it on really good speakers, how the band actually wants to present it and wants people to hear it. You make all these efforts to have this reverb on this or this delay on that, and depending on the way you’re listening to it, the whole point of what you’re trying to do on the record can get lost and that’s just not good. There are good sounding records and they sound good in a different way, and that’s cool, that’s great, but something’s getting lost there and that makes me worried.

Drew Daniel: It’s not as exciting to talk about, but it’s just as real, that we lose competence. We were artists in residence at Oxford and we had a dinner with a bunch of academics and Martin was seated next to one of the four people in the world who can still speak the language of the Punic civilization. It was this weird thing to see a person who’s one of our last links to a form of knowledge that will disappear and wink out.

Martin Schmidt: She was about 85, too.

Drew Daniel: How many people are feverishly photocopying their punk rock zine and then uploading it to a blog but then they move and they change their connection, that website’s dead, then that link is dead, those image links are dead, and the lights are going out. If they had just given that collection, say, to a real material library it would’ve been accessible to some scholar. So the idea like, the Internet’s just as good and better, it’s not true.

Joe Meno: In some ways everything that Punk Planet was able to do was because people wanted to find out about music or find out about art or find out about writing that they couldn’t from other sources. Then because of MySpace and the Internet, not only could you find out about it but you could actually hear the bands.

So it felt like these two different media crossing paths and there was a moment when it became clear, this is where the media is going, this is where the audience is going. Now I love print, but I also like to hear bands and I’m a huge music fan, so to be able to have that instant gratification of, “Here’s a band, let’s hear what they sound like,” is really alluring too.

I think now with the iPad and the Kindle, I’m not worried about print. I think print, there’ll always be an audience for it. It might be a smaller one, it might not even be the popular one, but it’ll always be there, just the way that bands still put out records on vinyl. There’s even a growing audience for that because people want things they can hold onto.

The Internet is great, but it’s ephemeral. You can’t put it in your house, on your coffee table. You can’t put it on your bookshelf to try to impress somebody the way you can put Gravity’s Rainbow and people are like, “Oh, you must be well-read, you did Gravity’s Rainbow.” You can’t really do that with the Internet. People like objects. I feel confident that books will be around. You look at somebody like McSweeney’s and just how sharp and smart they are at trying to keep people engaged with the book as an object.

It’s not a decline so much as an opportunity. People enjoy reading, whether it’s on a digital reader or in print form. I just want people to keep on reading. As long as they’re doing that, I don’t care what form it takes.

Vice Cooler: With music and print, like most creative things, what’s important is that it’s being created at all. I don’t have a preference of digital versus vinyl versus CD. I don’t listen to CDs much anymore, but I listen to vinyl, I listen to cassettes, I listen to mp3s, I download stuff illegally. But I also perform a lot, so to me mp3s and people downloading stuff means that people are going to come to the show. Or that’s the hope at least. And I think even arguing or debating about it’s useless because it exists. It’s pointless; it’s here and that’s the way it is.

Matt Gibson: The bottom line is: as an artist, whether you’re a visual artist or a musician or whatever, you should be creating and producing constantly. And as a listener or an audience member, you should be looking and listening constantly. So if that means go on the Internet and find something you like, or find a friend and just move it over to your thing and you haven’t paid that artist, I don’t find that to be a big deal.

I’ll say this, the artists who I’ve downloaded are either dead, or are super fucking rich anyway. So my conscience is clean. And then the people who aren’t rich, they’re my friends and we’re trading music anyway.

Billy Dufala: But then again, a great thing about the oversaturation technological age: blogs, man. Fuck dude, you got so many people posting the most amazing shit that you’d never get because it never even made it off of vinyl. You can just get lost on that shit for fucking weeks, if you had the time to be on a laptop and downloading tracks off of blogs.

Russell [Higbee] has shown me some of the most amazing music that he just got off these insane African blogs. It’s all crazy record collectors posting things every other day and being like, “Take it. Proliferate this. Know it exists.”

Matt Gibson: Anytime there’s a weird like, “What’s going to happen, no one’s buying music anymore,” that’s coming from the record label dudes that have been trying to make money off of musicians for their entire career. I don’t buy for a second that any musician is going to care this way or that.

Obviously there are record sales that are going to be hurt. You’re going to lose X amount of thousands of record [sales, but] we’re all in it to play and for people to listen.

Billy Dufala: We’re all in it because we are in a recession. It’s not just the music industry, it’s everybody.

Matt Gibson: Exactly, you just keep doing it. I feel like it’s all coming down from an executive level when it comes to that. “How are we going to sell this? How are we going to sell this?” I feel like if you continue to listen and then also turn around and create, I think it’s fine that we can all share music and images. Obviously when you go to an art show you’re going to see the work there in person. When you go to a live show you’re going to see the work there in person. And then if you’re still that interested, you’ll take home a record and that’s your contribution to the artist. And to the record label, more so. {laugh}

Share this post